-

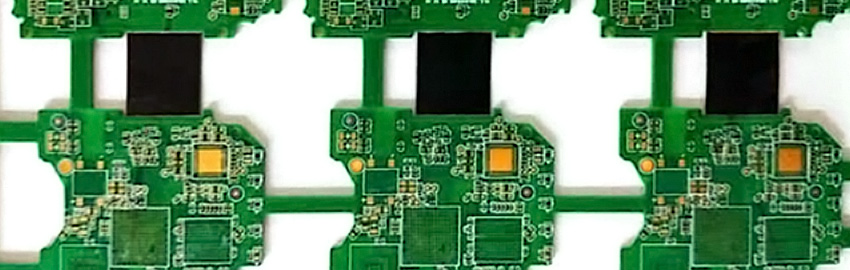

NTI-100: The World’s Top PCB Fabricators

The changing map of PCB production. READ MORE...

-

Elements of PCB Panelization

Panelize to optimize: faster builds, better boards. READ MORE...

-

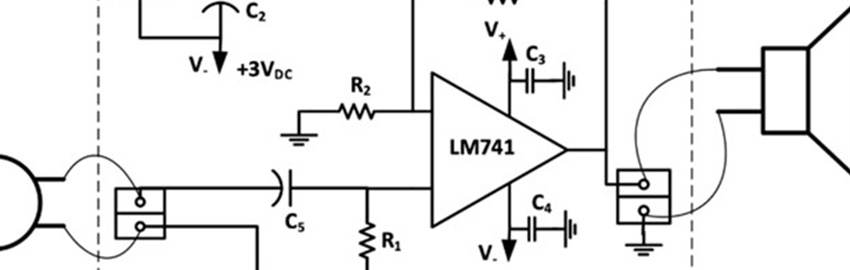

Optimizing Mixed Signal Circuit Designs

Navigating the analog and digital worlds. READ MORE...

-

Dynamic Times

Component Dynamics is where market intelligence meets distribution.

READ MORE... -

Power Circuits

Making power connections is a world unto itself. READ MORE...

-

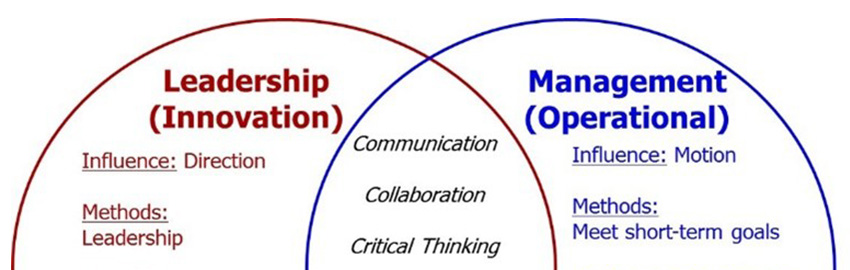

Developing Organizational Culture for Troubleshooting

Solving problems and adding value. READ MORE...

Homepage Slideshow

NTI-100: The World’s Top PCB Fabricators

The changing map of PCB production.

Elements of PCB Panelization

Panelize to optimize: faster builds, better boards.

Optimizing Mixed Signal Circuit Designs

Navigating the analog and digital worlds.

Dynamic Times

Component Dynamics is where market intelligence meets distribution.

Power Circuits

Making power connections is a world unto itself.

Developing Organizational Culture for Troubleshooting

Solving problems and adding value.