Fine tuning the timing of net groups.

Fine tuning the timing of net groups.

When faced with a microcontroller and a companion memory chip, to unravel the crossed-over connections while maintaining high quality microstrip and stripline connections can be a daunting task. Add in the requirement around the time of flight for a typical memory bus or other family of high-speed connections, and you can spend considerable time sorting out that nest of interconnections.

As PCB designers, we go to great lengths to meet the requirements for additional air gaps around transmission lines. Isolating one trace from another becomes more important as the overall length of the traces grows. Crosstalk is a function of how far two traces run parallel to each other at a given distance apart. So, ultimately it is more than the minimum air-gap in play. The length of the boundary also matters.

With a number of connections that start in one general area and end at some other location, it’s easy to picture a river of traces running from here to there. The variance in length between any of the routes is small compared to their total length. Any traces on the long side get pulled tight to minimize their natural length. From that point, the traces that end up too short get some meanders along the way.

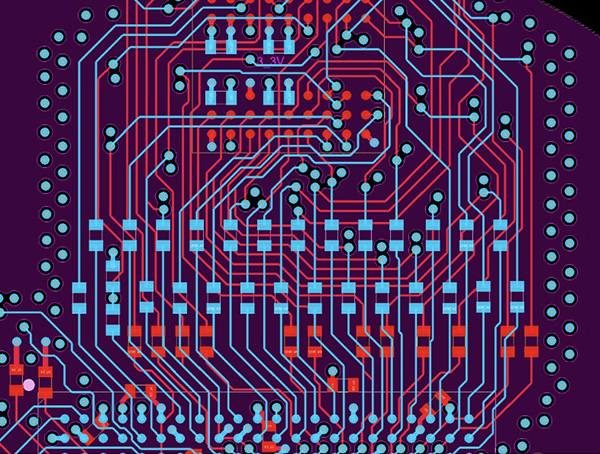

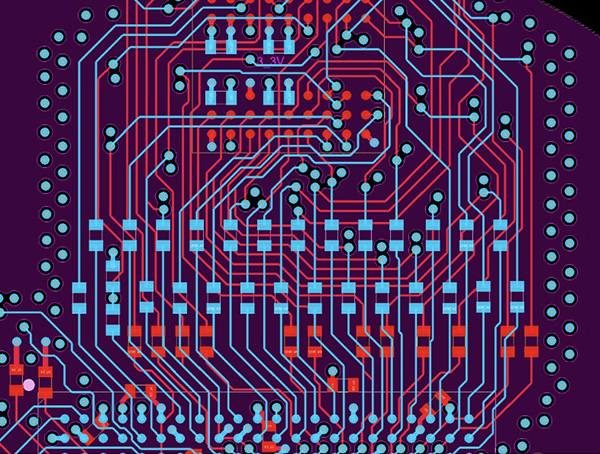

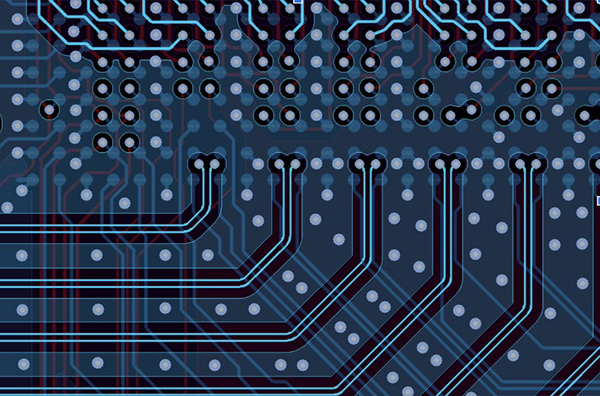

Figure 1. Flash memory data lines with series resistors routed on the top and bottom layers. (Source: John Burkhert Jr.)

Differential pairs – A noise abatement program. It takes two to start a group and quite often, that’s all it takes to form a group of PCB connections. So-called differential pairs exist when the duty of sending a stream of data is shared between two complementary traces. They generally run side by side as edge-coupled diff-pairs but can also be done using two adjacent layers using broadside coupling.

Either way, they are length-matched as best as possible to bring the two signals to the end of the route at the right moment. Generally, a symmetrical launch from pins and vias helps and is strongly recommended for avoiding an impedance mismatch. The idea behind differential pairs is that any transient noise in the vicinity of the signal shocks both lines during the instant the waveforms are transiting any specific location. Then we can recognize the difference between a high and a low logic state at a higher rate and over a longer distance owing to the noise immunity. That’s what makes today’s world go around.

Phase matching for differential pairs. Given there are two traces running along together, it’s inevitable one will have an inside path through any bend. Depending on the data rate, that may be enough to get the two signals out of sync, especially if a bend to the left is not immediately canceled out by another to the right. In this case, it’s not enough to match the total length. We compensate with a small bump on the trace that has the inside line keeping the signals running neck-and-neck the whole distance. When the rise times are that severe, it’s best to minimize trace bends in the first place.

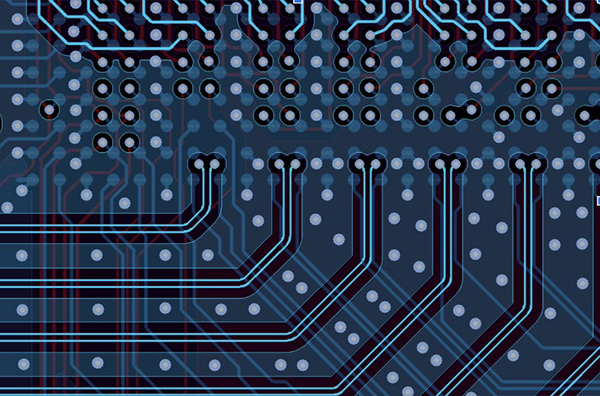

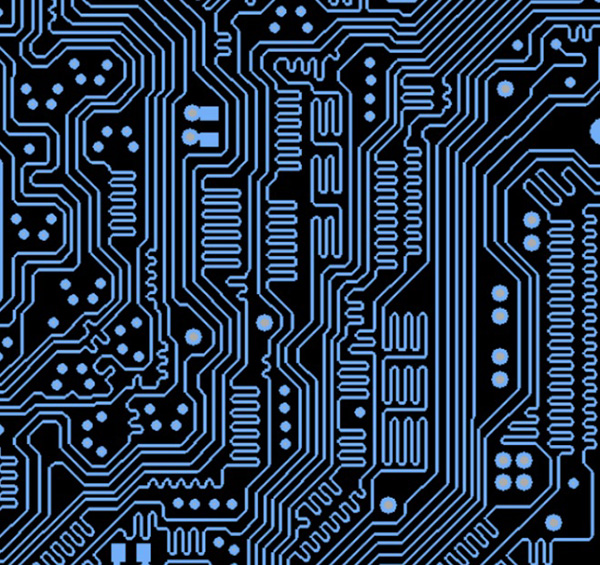

The thing about differential pairs is they like company. There’s always more than one pair. Once we’ve solved inter-pair skew, we get to the intra-pair skew between respective data lanes. A general observation is that when there are fewer members to a match-group, the length tolerance budget is tighter. Something with between two and eight pairs is likely to require fine tuning with the data likely being serialized (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Differential pairs routed in separate channels for isolation. (Source: John Burkhert Jr.)

That’s not to say that a wide bus is necessarily going to have significant latitude on length matching. In many cases, the large number of group members is subdivided into data lanes of perhaps 8 or 16 bytes that are each under the aegis of a dedicated clock net. There can be a lot of clocks and they all want extra breathing room.

General length matching strategy. My process begins with generous length matching tolerances as a way to get the data lines into the same neighborhood as the clock. Once everything is close, you’re not far from finding the length value that all the connections can meet.

Must all the lines in the bus be the exact same length? No, but if you start with that goal, you’ll end up with a smaller spread. I try to center-cut the tolerance band to match all lengths if there is sufficient room. Otherwise, my clock is as short as it can be while just long enough to solve for the longest data line. That would be space efficient but also brittle, as some small bump could throw the length matching out of kilter. Matching them all on the money is more resilient and easier to defend in a design review.

Between LiDAR sensors, AR headsets and sat-comms, the number 128 has come up every time. They all had to convert 128 analog streams into digital representations. One used four big 32 channel ADCs while the others made do with 16 ADCs that had eight channels each. Automotive, defense or space: all had to be hardened for tough environments. In each case, the better we could do in hardware, the less work for the processor. There are applications with two or four times this many lines. Let me know if you’ve heard of any buses with over 512 members.

In terms of the sensor, the single-ended inputs exited the ADCs as differential outputs and had to be tuned to the point of eliminating variance. Studying the layouts prior to fan-out and colorizing the nets that appeared to be the long tentpoles is step one. Giving those long traces priority during routing is the forward-looking strategy.

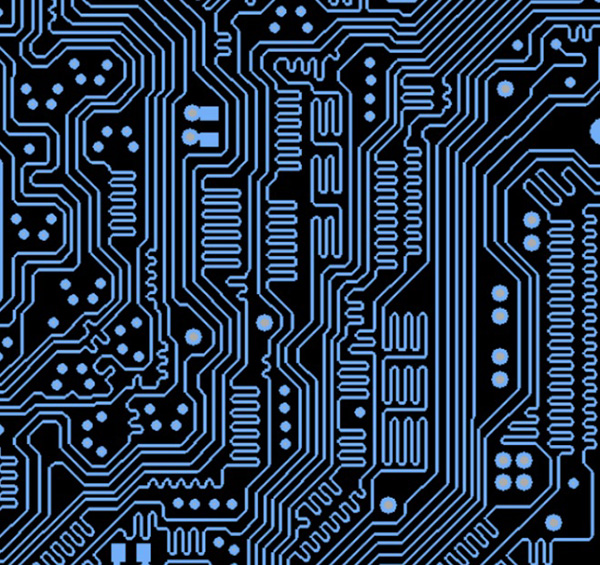

Other traces to look out for are the ones that run along the outside of the bus. Those lines define the space taken by that particular bus. As much as possible, it pays to create a guard band to separate the group from the outsiders. The space within must permit all the meanders for the present conditions and some wiggle room so that a minor design update with “one more via” doesn’t break the design (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The telltale foursomes of vias (at left) that transition the differential pairs while the right side had the dense meanders that I would caution against if you have any choice. This was a case of severe mismatch. (Source: John Burkhert Jr.)

What does success look like? After a routing study or two, the most natural and elegant solution should come into view. Nothing is perfect, and even if it is, there will be reasons to chip away at the board space until it becomes a concern. So, when the traces are escaping the big device or some other pin-field, a few close encounters are unavoidable. Being mindful of the crosstalk; the closer the elements get, the sooner and more they need to diverge.

A clean bus looks undisturbed with an almost hypnotic neural procession of connections. The fan-out may not be symmetrical, but the underlying connections go from station to station with no further crossovers or layer changes. The turns are few and purposeful. The spacing prevents ground pour from getting into recesses where no support via can tie it down. The balance of copper and air across the bus is optimized to isolate the maze of lines. The warts are few and have been considered acceptable.

No plan survives contact with the supply chain. Iterations will come from the development team, so always be ready to rip up your best work. Whether driven by simulation results or the endless supply-chain drama, we often have unscheduled work to do – and on short notice. If you’re a player in this game, you should recognize the trend. A board that meets the requirements in the digital realm relies on good routing techniques. Use those and produce acceptable results quickly.

One way to get a leg up on co-development is to dig into the constraint manager and make it do some of the work – and verification – for you. From experience, it gets harder to remember everything as the years stack up. Memorializing the design rules so you know how much you can alter them and stay within the specification will help the future version of yourself. Do that person a favor; capture the design intent.

John Burkhert Jr. is a career PCB designer experienced in military, telecom, consumer hardware and, lately, the automotive industry. Originally, he was an RF specialist but is compelled to flip the bit now and then to fill the need for high-speed digital design. He enjoys playing bass and racing bikes when he’s not writing about or performing PCB layout. His column is produced by Cadence Design Systems and runs monthly.

Fine tuning the timing of net groups.

Fine tuning the timing of net groups.