Knowing what information to include will simplify the assembly process.

So you’ve got a great idea and you want to bring it to market, but you don’t know the first thing about hiring a manufacturer and working with them to get your product assembled? We are here to help. This is the first in a series of columns on how to get product assembled.

What’s a BoM? Well, you probably already know what a BoM is (bill of materials), but what are we specifically looking for from a BoM?

There are three vital pieces of information:

1. Reference designator. This will be the location of the component, something like R1 for resistors or U1 for ICs. Begin with a prefix and then assign a unique number. Here are the common prefixes:

- Capacitors “C”

- Connectors “J”

- Diodes “D”

- Displays “DISP”

- Ferrite Beads “FB”

- ICs “U”

- Inductors “L”

- LEDs “LED”

- Modules “U”

- Oscillators (Crystals) “Y” or “X”

- Resistors “R”

- Resistor Networks “RN”

- Switches “SW”

- Test Points “TP”

- Transformers “T”

- Transistors “Q”

2. Manufacturer’s part number. The assembler needs to know what part to put in the location you’ve specified, and what we look for is a specific manufacturer’s part number. Saying “100k ohm resistor” isn’t quite enough information. Think for a second how many pieces of information need to be specified for just a resistor: value, tolerance, size, wattage, composition, temperature coefficient and operating temperature. And that’s just for resistors! It’s more information than we’d like to decide for you. An excellent resource is the Common Parts Library, which WAi helped assemble in partnership with Octopart. We regularly keep these parts in stock and find them to be readily available and inexpensive compared to their alternatives.

3. Quantity. This is helpful for purchasing purposes. If you used a 1k resistor in 90 different locations, we’d rather not count those locations one by one to determine how many of that part number to buy. The quantity column will also help us double check our work. If we program our equipment and it tells us there are 89 locations and you have a quantity of 90 specified, that will send up a red flag that there might be an issue. Some of our customers put plenty more information in their BoM that is useful but inessential.

4. Line Items. This is handy for communicating back and forth. If we mention “there’s a typo on line item 16,” you’ll know exactly where to look at your BoM for the issue.

5. Descriptions. Descriptions are really helpful. Internally, we use DigiKey’s descriptions as much as possible because they are formatted nicely and have all the pertinent information. We can also use the description to make sure your manufacturer’s part number is correct. If your description says it should be a 4.7k resistor, and we look up the manufacturer’s part number and find it’s a 47k resistor, we can check to verify you’ve chosen the correct part number. You’d be surprised how many mistakes are caught with this technique.

6. Datasheets. It’s useful to have a hyperlink to datasheets for components. Sometimes manufacturers don’t publicly release their datasheets. (I’m looking at you, Broadcom!) Providing a link to datasheets helps speed the process of programming the board. But don’t stress about it. It’s not necessary.

7. Hardware details. Providing a nice full description of a piece of off-the-shelf hardware is great. If you give us a part number from McMaster-Carr for a hex nut, that’s great. But a good full description of the nut is even more valuable. Is it stainless steel or galvanized? Is it 3/16", how many turns per inch, etc.? When we have a full description, we can confidently buy these parts from an alternative manufacturer. I love McMaster-Carr. (Seriously. I love McMaster-Carr.) But they’re expensive. And we can find hardware for far less money from other suppliers.

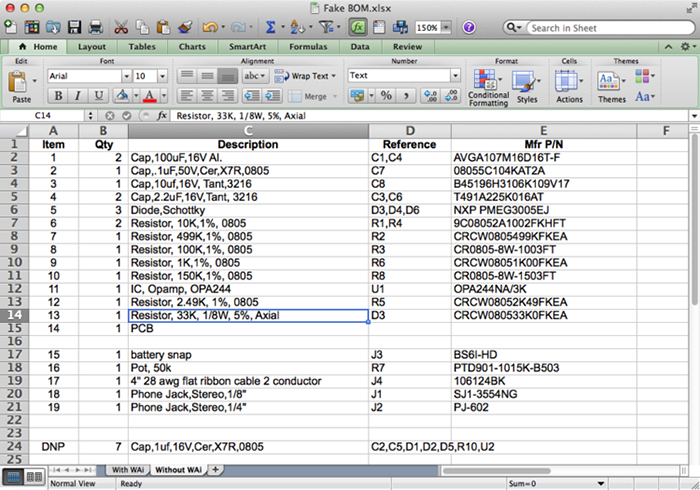

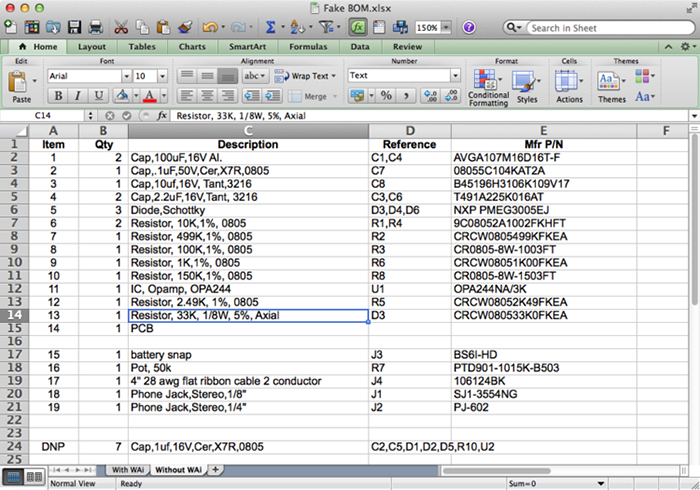

When you’re done, a BoM will more or less look like FIGURE 1. It generally is formatted as a table that can be parsed by Excel or another spreadsheet program. CSV files and tab separated files work great too. We’d honestly prefer them over a proprietary format like Excel or OpenOffice.

Figure 1. Example of a BoM (bill of materials).

Chris Denney is CTO of Worthington Assembly Inc. (WAI); This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..