-

The Trade Show Connection

Finding community amid chaos. READ MORE...

-

Understanding ANOVA

Analyzing process data for accurate, defensible decisions. READ MORE...

-

High Yield Design Practices

Building with manufacturing limits in mind. READ MORE...

-

Rigid-Flex Design

Rigid-flex technology is redefining electronics design. READ MORE...

-

PCB Thermal Challenges

When passive heat management isn’t enough. READ MORE...

-

NTI-100: The World’s Top PCB Fabricators

The changing map of PCB production. READ MORE...

Homepage Slideshow

The Trade Show Connection

Finding community amid chaos.

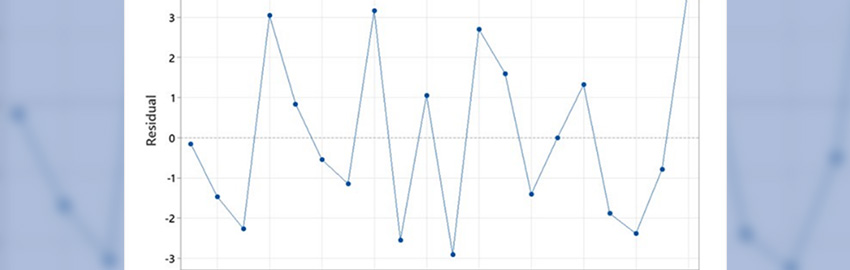

Understanding ANOVA

Analyzing process data for accurate, defensible decisions.

High Yield Design Practices

Building with manufacturing limits in mind.

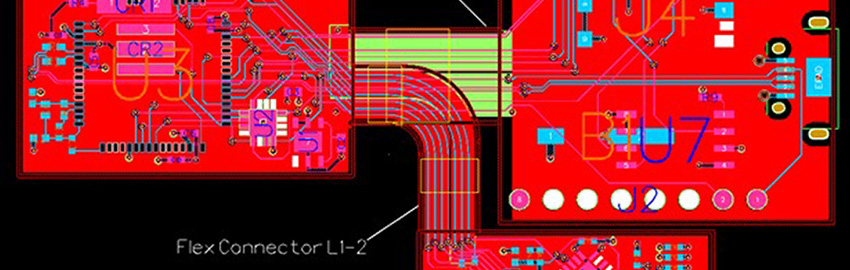

Rigid-Flex Design

Rigid-flex technology is redefining electronics design.

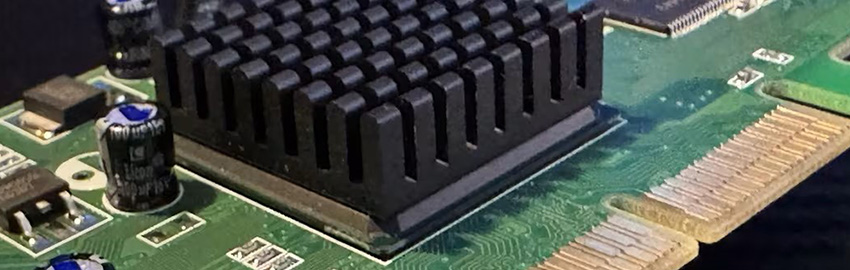

PCB Thermal Challenges

When passive heat management isn’t enough.

https://pcdandf.com/pcdesign/index.php/current-issue/241-designer-s-notebook

NTI-100: The World’s Top PCB Fabricators

The changing map of PCB production.