3D printing will have a big impact on everyone in years to come – whether they realize it or not.

Working with some of the world’s leading product innovators, we’ve gained insight into the potential benefits, such as saving the lives of babies.

About eight out of every 1,000 newborns are born with congenital heart defects — variations from a normal heart’s structure that change the flow of blood through the heart. Congenital heart defects can be grouped into broad categories but the detailed heart structure of many babies born with defects is unique.

The most serious of these defects have such a major impact on the functioning of the heart that the baby’s long term survival is in doubt without correction of the defect. Correcting the most serious defects requires surgery to make major changes to the heart and arterial system. Often these surgeries are so encompassing that they require multiple procedures extending over the course of several years.

Surgeons treating these babies are often faced with the challenge of correcting a problem unlike one that they have seen in the past. Frequently, multiple specialist teams are involved in these interventions so the challenge extends to coordinating the work and gaining agreement of each of these teams on the best path for correcting the defects.

Surgeons traditionally work with sophisticated imaging systems including echocardiography and computed tomography (CT) angiography to study the hearts of infants with defects and plan the operations. But the 3D complexity of the heart is so great that it’s often difficult to fully understand the geometry of these hearts and plan corrective surgery when the surgeons are limited to looking at a 2D computer screen. In the worst-case scenario, surgeons are forced to make changes on the fly during surgery, which increases the length of the procedures, adding to the strain on the babies’ fragile bodies. David Escobar, who currently works as a Lead Simulation Specialist at a major Southern California hospital, is spearheading the drive at his institution to implement 3D printing to improve the process of planning for surgical correction of congenital heart defects and other healthcare applications.

“With 3D printing we can create a 3D physical replica of the patient’s heart that the physicians can hold in their hands to visualize the operation to a much higher degree than is possible with an image on a computer screen,” Escobar said. “Surgeons can manipulate the 3D model to practice the surgery in advance and make measurements to configure the necessary (devices, or stents) with the exact shape and dimensions to match the patient’s heart. This makes it possible for the surgeons to enter the operating room with a higher level of certainty. In some cases, this leads to a more favorable outcome because the amount of time that the infant must spend in surgery is reduced.”

“The surgeons that I have talked to all speak highly about the benefits of 3D printing and I have seen individual cases where it has saved lives,” Escobar said. “3D printing also makes the patients’ families feel more comfortable because the surgeon can do a better job of explaining the procedure with the model as a visual aid.” Escobar added that several clinical studies are underway to determine whether 3D printing can provide quantitative benefits in surgical planning but are a long way from providing conclusive results.

Figure 1. Airway with prototype inserted.

In the meantime, hospitals are not able to obtain reimbursement for 3D printing expenses so Escobar’s institution, like many others, is forced to proceed on a shoestring budget in implementing the new technology. Escobar has addressed this challenge by working with low-cost consumer-grade 3D printers. He has obtained several grants to study the use of 3D printers in various medical research applications. He has also used the hospital’s 3D printers to perform work for hire for other companies and institutions to assist in covering their costs.

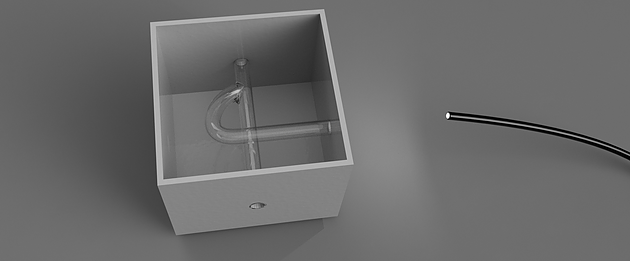

Figure 2. Difficult airway modification prototype.

Escobar developed a custom 3D printed piece that helps improve the realism of a high-fidelity manikin used to train physicians in skills such as endotracheal intubation, the placement of a flexible plastic tube in into the trachea or windpipe to maintain an open airway or serve as a conduit to administer drugs. One of the training scenarios in Escobar’s institution’s healthcare simulation center was to replicate a situation where it is very difficult to pass the endotracheal tube into the patient’s trachea. But the manikins used by the hospital provided very little resistance to intubation. Escobar created a custom 3D printed piece that fits into an opening behind the vocal chords in the manikin and provides more realistic resistance to passing the tube.

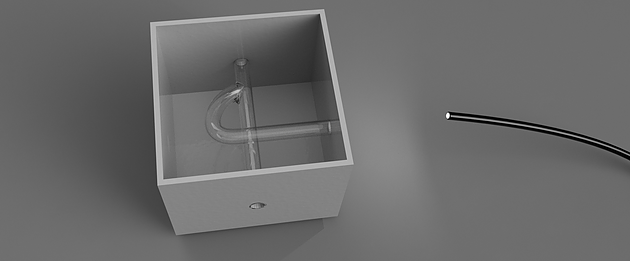

In another application, Escobar worked with a team of surgeons to create a more realistic model to train medical residents in endoscopic surgery. “Starting with a rough drawing, I was able to not only design but prototype a training model that is now being used with all new medical residents in my healthcare organization,” he said. “Being able to print and share the design with the team provided a quick turnaround time. ”

Figure 3. Endoscopic trainer.

“3D printing has already demonstrated major benefits in a wide range of medical applications including surgical planning, medical models, low-cost prosthetics and custom medical equipment,” Escobar concluded. “Many interesting new applications are on the horizon such as printing cranium replacements, synthetic bones and heart valves. In the next few years I predict that 3D printing is going to take on a much greater role in healthcare, resulting in better patient outcomes and lower healthcare costs.”

The post 3D Printing Helps Save the Lives of Babies Born with Congenital Heart Defects appeared first on Zuken Blog.