PCB manufacturing doesn’t have a talent shortage; it has a marketing problem.

PCB manufacturing doesn’t have a talent shortage; it has a marketing problem.

Where are all the PCB youngbloods? Why aren’t young men and women entering the industry in the numbers they did in the past?

I asked these questions several years ago, and the situation has improved slightly since. But not enough.

The average age of PCB fabrication workers continues to climb. Industry surveys now peg it somewhere north of 50 years old, and the pipeline of replacements remains dangerously thin. We’re not just facing a skills gap anymore; we’re staring down a demographic cliff.

I suspect the shrinking and consolidation of the domestic industry, along with the pessimism of many who’ve stayed in it, is at least partly related to the vanishing of younger colleagues. But I’ve come to realize the problem runs deeper than industry morale or even offshore competition.

The brutal truth? We’re being out-recruited, out-messaged and out-glamorized by every other sector of the tech economy. When a computer science graduate can walk into a software startup offering north of $80,000 in starting salaries, stock options and the promise of changing the world from a Herman Miller chair, how do we compete while offering a facility that smells like copper etchant?

The compensation gap has widened. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, median pay for electronics engineers in the semiconductor and PCB sectors has lagged software and digital sectors by 15-20% over the past five years. For technicians and operators, the differential is even starker. A young person with decent STEM aptitude can earn more managing a Chick-fil-A than working on a PCB production floor in many regions.

But money alone doesn’t explain it. The semiconductor industry – our cousin sector – has managed to generate excitement despite similar manufacturing realities. TSMC’s Arizona fabs are attracting young talent. Intel’s Ohio investments are creating buzz. Why? Because they’ve successfully marketed themselves as essential to national security, AI advancement and technological sovereignty. The CHIPS Act didn’t just bring $52 billion in funding; it brought legitimacy and visibility.

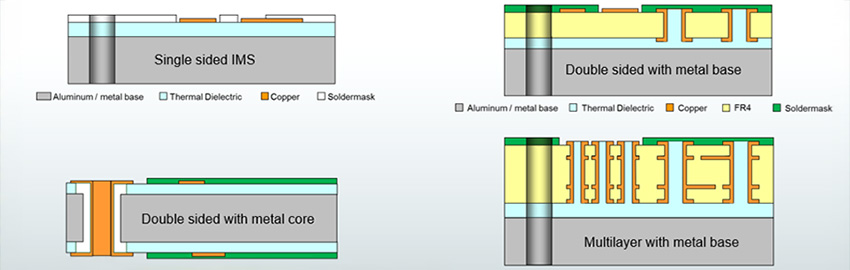

Meanwhile, PCBs remain tech’s version of Rodney Dangerfield – no respect – despite being the foundation of every electronic device. Your smartphone’s processor gets the glory; the multilayer board it sits on gets ignored. That coveted Tesla? It has more PCB surface area than a 1990s desktop computer, yet no one talks about it.

The CHIPS and Science Act’s focus on supply chain resilience has put renewed attention on PCB capabilities. America’s defense leaders are finally acknowledging that advanced circuit boards are a strategic vulnerability – we can’t build secure systems using exclusively overseas fabrication.

The educational pathway has fractured too. Technical schools that once fed our industry have either closed or pivoted toward IT and software. Community colleges offering electronics programs have seen enrollments crater. High schools have largely eliminated shop classes and hands-on technical education in favor of college-prep curricula. We’ve created a generation that can code Python but couldn’t identify a via if their life depended on it.

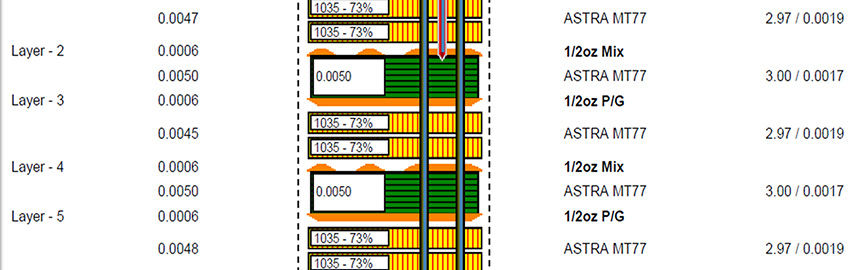

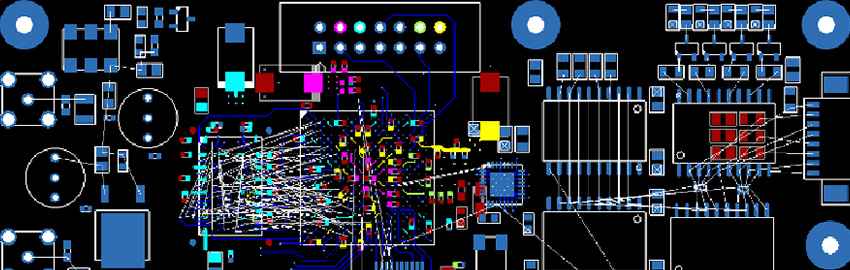

There’s also an image problem we refuse to confront. Manufacturing, especially PCB manufacturing, is still perceived as dirty, repetitive and dead-end. Never mind that modern fabrication facilities are climate-controlled cleanrooms using advanced automation. Never mind that process engineering requires sophisticated problem-solving skills. Never mind that someone who masters imaging, plating and etching processes understands more practical chemistry than most pharmacists. The stereotype persists: manufacturing is for people who couldn’t make it in the "real" tech world.

The industry’s scattered geographic footprint doesn’t help. Unlike software hubs in Austin, Seattle or Silicon Valley, where young professionals cluster and create culture, most PCB fabs are distributed across suburban and rural areas. It’s hard to recruit 25-year-olds to facilities located on the edge of towns when their peers are building lives in vibrant metro areas.

Yet there are glimmers of hope.

At PCB West in Santa Clara in October, I saw more youngbloods than ever before. They were impressive. Most of them, however, were involved with PCB design, designing products or companies that rely on software rather than manufacturing solutions for their customer.

The Printed Circuit Engineering Association (PCEA) is working in partnership with Michigan’s Wayne State University, offering training and certification courses in PCB design. Calumet Electronics, a PCB manufacturer also located in Michigan, has been very vocal about its outreach program to attract youth to our industry. And the Global Electronics Association (GEA) trade group, formerly known as IPC, has been promoting the recruitment of young talent as well.

But these are scattered efforts, not a coordinated campaign. What we need is an industry-wide initiative that repositions PCB careers as what they actually are: essential, sophisticated, well-compensated pathways into advanced manufacturing that will be crucial for the next thirty years of technological development.

We also need to face facts: some young people will never be interested in manufacturing, and that’s fine. But there’s a massive cohort who would thrive in this field if they knew it existed, understood what it entailed, and saw a viable career trajectory. We’re losing them not because they’ve rejected us, but because we never showed up to recruit them.

So I’ll ask again: Where have all the youngbloods gone? It’s true a few more are around. Not nearly enough, though. What are we – the veterans, the owners, the industry associations – willing to do to bring them back?

Greg Papandrew has more than 25 years’ experience selling PCBs directly for various fabricators and as the founder of a leading distributor. He is cofounder of DirectPCB (directpcb.com); This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

PCB manufacturing doesn’t have a talent shortage; it has a marketing problem.

PCB manufacturing doesn’t have a talent shortage; it has a marketing problem.