The PCBAA is ramping up efforts to secure funding for R&D and capacity in the US.

What constitutes the printed circuit board industry? And how much, if any, investment should the US government allocate toward ensuring its technological and capacity capabilities?

These are among the questions David Schild is tackling every day. Schild is executive director of the Printed Circuit Board Association of America, which was founded in 2021 to advance US domestic production of PCBs and base materials. The organization is made up of corporate members of all sizes and includes fabricators, assemblers and suppliers.

Schild addressed questions about public and private investment, how governments can help create "demand signals," and the PCBAA's annual meeting with PCEA for the PCB Chat podcast in late July. The following transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Mike Buetow: You came to PCBAA in November after years spent serving the aerospace and defense industries. [In June] PCBAA had its annual meeting, which I believe was your first as executive director. Let's get your initial thoughts on that meeting and the priorities that came out of it.

David Schild, PCBAA executive director

David Schild: This was our second annual meeting in Washington, DC. As you mentioned, we're a new association but growing rapidly. We doubled year-over-year from the 2022 to the 2023 annual meeting. And I was just thrilled that so many of our leaders gave their time and their talent for a couple of days in Washington, both to hear from the experts – officials from the Department of Commerce and from the Department of Defense, elected officials and staff from both the House and Senate – but also to do the hard work of lobbying, to go up to Capitol Hill and wear out the proverbial shoe leather so that we can advocate for our industry. Great meeting.

MB: Several industry leaders sent a letter in June to the Appropriations Committee and the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee in the US Congress. In it, they pushed for $100 million in the next budget to implement President Biden's designation of printed circuit board and IC substrates as technologies that are critical to US national security. What has to happen to make this a reality?

DS: I'm glad you brought this up. The invocation of the Defense Production Act was a long-time legislative priority for our group, and our coalition more broadly. It's great to see at the highest levels of government an official designation that printed circuit boards and IC substrates are critical national assets. We share that view completely now. We have to invest the money. The DPA is really a hunting license and, once it's granted, you sort of have to put some bullets in the gun, some arrows in the quiver, as it were, and what we're looking for is a $100 million appropriation that would go to the Department of Defense budget and that would allow investment in rapid prototyping, research and development, the kind of things that we're going to need to invent the next generation of technologies in this particular segment. The appropriations process is something that happens every year. Everybody and their brother is looking to add monies to that process, but certainly we're going to push hard for this $100 million as a down payment. It's not all that we need, but the Department of Defense recognizes that next-generation microelectronics are going to power everything that our war fighters use, and we need a strong domestic capacity to produce those technologies.

MB: Would that $100 million be part of the National Defense Authorization Act?

DS: No, I'm glad you mentioned that. There's a distinction between the NDAA, which is an authorizing document, writing out policies, procedures, and guidelines for the Department of Defense. I'm oversimplifying, of course, [but] for the appropriations process, we have a bill for pretty much everything the government does, from agriculture to education to defense. We need the policy language that's in the NDAA, and I can talk about more specifically what hits printed circuit boards, and we need actual dollars appropriated through that annual appropriations process.

MB: OK. I want to circle back to the NDAA in a moment, but let's just say that $100 million appropriation happens. What does the roadmap look like insofar as where it's applied? In other words, why $100 million and how would it be spent? For instance, there's been a lot of focus on chiplets of late, but of course most US manufacturers have little to no experience building that technology. Would that be a focal point?

DS: I think anything that's an emerging technology is something the Department of Defense is looking at. I don't want to speculate too much on how that money would be specifically allocated because my sense is that the DoD is going to open the window, as it were, and they're going to say, "Hey, come to us with your ideas, with your proposals." [There are] several offices within the Department of Defense, in the acquisition technology and logistics space; you have an Executive Agent dedicated to printed circuit boards out of Crane in Indiana and these offices, I think, want to see companies stepping up with proposals to say, "This is the problem that you've designated, and this is our technology solution." That $100 million can get used up pretty fast on cutting-edge prototypes and research and development. But if we were to mirror the way it's been done in the past, I think you would see the Department of Defense saying specifically, "These are the problems that we need to solve, industry. What are your solutions and what do you need to make that happen?" And there would be a call-and-response there. That's what we've seen with other smaller allocations like this.

MB: So the expectation would be, then, companies would go to the US government and apply in the form of grants or other kind of funding for that money? Or would there be a third party that would be responsible for allocating it?

DS: Typically the Department of Defense will make direct investments. Different government agencies do it differently. And again, I don't want to get too much in the weeds about the procurement process and how some of these grants would work. The Department of Defense does have a different process than, say, the Department of Commerce, which is administering the CHIPS program. But I think that they understand that all these future technologies are going to power everything from submarines to satellites, and there is a concern about the industrial base, right? What you see at the Department of Defense when they talk about these kind of investments is thinking not just six months, but six years or even 60 years ahead to say, "Hey, can we make the things that we need for future conflicts, future challenges that the department might face?" They're trying to get ahead of a problem right now.

Our industry does a tremendous job of meeting the need for secure and trusted microelectronics that go into everything that floats or flies, as we say. But I think there's a concern about the next-generation technology set. Are we going to invent it here in America? Because if it's not invented here, we become deployment-dependent on foreign sourcing. That obviously makes the DoD nervous. Hence, the desire to make some of these initial investments. And again, this is an industry push for the $100 million. This is our industry saying, DPA simply allows you to spend. Now let's put our money where our mouth is.

MB: Do you think the actions going on right now in Ukraine and Russia have created any kind of sense of urgency among the congressional members insofar as saying, "Wait a minute. If we're seeing how much supply we're using for something that we're not directly involved in, what do we need to do to ensure we have the capacity if we are directly involved?"

DS: Two things are happening simultaneously. I'm glad you brought this up. Number one, there's a greater recognition of the high-tech nature of modern weapon systems. The conflicts of today and into tomorrow are being fought with extremely high-tech systems that rely on, among other things, microelectronics. Certainly, we're not the only industry that has some light shining on it right now. You see critical minerals. You see specialty metals, alloys, even issues of workforce, labor concerns: Do we have enough people who can do these special skills? So one, I think everybody sees what's going on in that particular conflict and says, "OK, high-technology munitions, high-technology defense systems, this is the way that battles are being fought."

The second part of that, I think, is an understanding that we are burning through some of our stockpiles. We are making significant debits against some of our inventory and those are going to need to be replenished. Again, I'm not hearing any problems right now meeting the demand coming out of the Department of Defense. What I think we recognize is that defense-focused industries often need their commercial partnerships, their commercial side of the factories, to keep everything healthy. You see this with military engines, at companies like, let's say, Pratt and Whitney, you see this with national space applications where if commercial launch is suffering, defense launches face challenges. I think there's a similar analogy in our industry where we want to have a commercial space that is healthy, that is productive, that is profitable, because it enables the defense line, which is much smaller, much more bespoke, to be sustainable.

MB: Now I want to point out that of the 26 companies that signed that letter, a third of them are primarily in the assembly space. So you're not just working to assist the fabrication side.

DS: No, absolutely not. PCBA has critical material suppliers, it has assemblers, it has PCB manufacturers and we're hoping to welcome more substrate companies, an emerging area of growth in the United States, a place that we've got to do better, I think 99% of our IC substrates are made overseas because upstream and downstream of the boards themselves, there is a real impact here. The $3 billion that our PCBs Act calls for would be available to anybody who makes boards or substrates, but the 25% tax credit is really the game-changer because it would apply to anybody buying American printed boards or substrates. So now you've got any company using these technologies saying, "I want to reassure, I want to diversify my supply chain. I'd like to buy more things in America. But it's not cost-competitive." The tax credit gets you there.

MB: Changing gears for just a moment, the bipartisan HR3249, better known as the Protecting Printed Circuit Boards and Substrates Act of 2023, is seen as a necessary adjunct to the CHIPS Act. Its goal is to incentivize investment in the US PCB industry. It calls for, among other things, $3 billion to fund factory construction and modernization, workforce development and R&D. And it also calls for a 25% tax credit for purchases of American made PCBs and substrates. I think it has five cosponsors so far. What can you tell us about the status of that bill?

DS: It's been referred to several committees of jurisdiction and we are building a strong base of support. I know that our coalition is meeting every week with lawmakers virtually and in person to appeal to them to support the bill. The more cosponsors we get, the more of a snowball effect that we build, of course. Congress has been consumed lately with spending bills, raising the debt ceiling, moving several critical bills like the NDAA forward. But I think what we are trying to do now is the educate part of our educate, advocate and legislate mission. One thing the semiconductor industry did very, very well was teach everybody how essential semiconductors are to modern life. We need to accomplish the same thing with printed circuit boards and substrates. We need to make people understand that there is a technology stack at work. That's one of the first conversations we have with members of the House and Senate: If I hold this green board up, do you understand its role in the ecosystem? Do you understand how critical this is? We used to make 30% of the world's supply here in America. Now we make 4%. That's an unhealthy contraction. That's a concerning dependence on foreign sourcing. And sometimes you see people's eyes light up and they're like, wow, I didn't know this. They of course know it about semiconductors. Our friends in the semiconductor industry did a tremendous job of getting the word out. We need to do the same thing. The PCBs Act will pick up more and more support, I'm convinced, once we explain to more and more elected officials our role in the ecosystem.

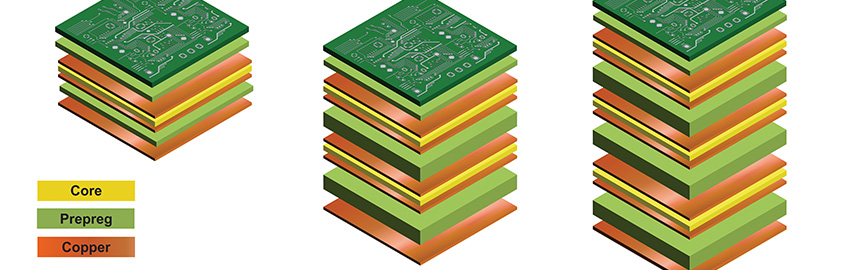

Figure 1. The success of the CHIPS Act is seen as a roadmap to the subsequent PCB bill.

MB: And that's 4% of the value of the output. It's not 4% of the total production output, which would be probably even less because that would be on a square foot basis. The volume of these boards being produced in Southeast Asia is so much greater than what we're doing here. They're just generally lower-cost boards.

DS: The President said something in the State of the Union last year that I really agreed with: "If we invent something in America, we should make it in America." We have been the leader in innovation in this space. One of the things that our chairman Travis Kelly talks about a lot is that research and development and design are often colocated with production. When you take a PCB or a substrate factory and you move it over, you can certainly produce a lower-cost good, but what happens is that the next-generation technology is being invented there colocated with production. We lose the capacity to build these things, but we also lose the know-how, the intellectual power that will design the next generation. That's why there's such an imperative to rebalance. No one is arguing that we should put up enormous walls and try to decouple from the world and undo a global economy that's 50 years in the making. I don't think anyone's making that argument. What we're saying is that 4% is simply not a healthy slice of the pie, and it presents real supply chain and security risks.

MB: I would agree 100% with what Travis is saying and in fact, if you look at companies like Apple, they have a huge number of manufacturing patents that they apply for every year, even though Apple doesn't "manufacture" anything. I think that there are companies that still recognize there's a strong tie between understanding how things are built and understanding what the next generation or a couple of generations down the road of design are going to look like.

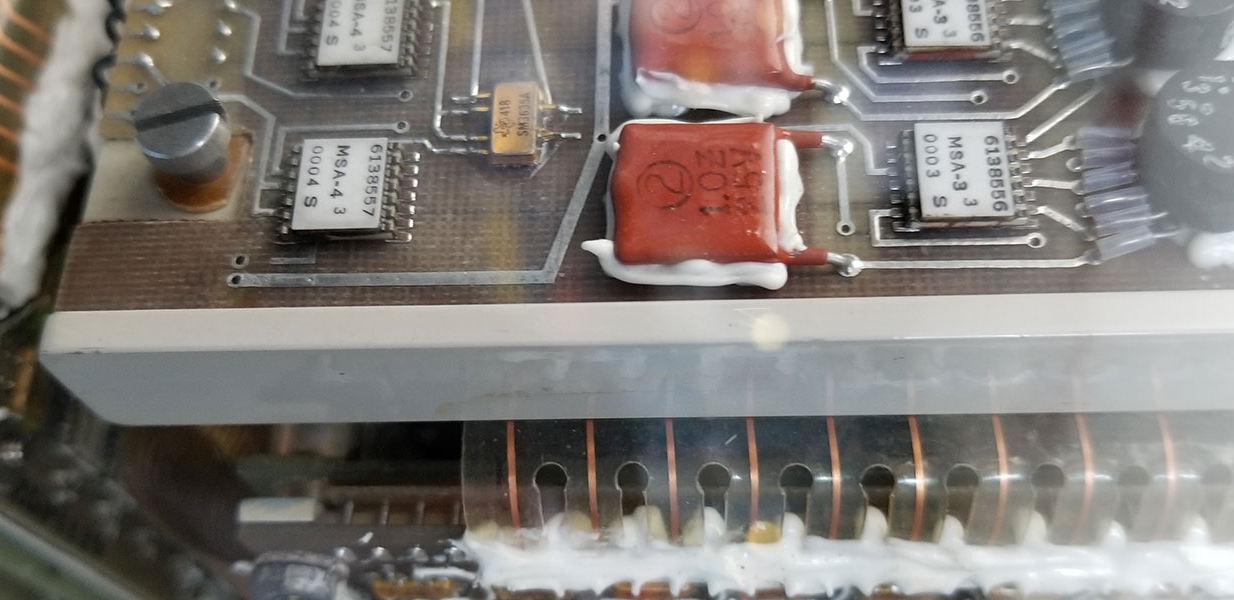

I want to circle back to something you mentioned earlier about the industrial supply base. I would argue that in the great successes, the transcendent moments in American history, there's a very close tie between the government and industrial partnership. If you go down to the US Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville [AL], you can see the first examples of surface mount boards. These are from 1964, and they are all built by IBM, not a defense contractor. Folks who were making computers had also figured out the manufacturing technology that was needed for the one-of-a-kind, at that time, space launches.

DS: We just passed the 54th anniversary of man landing on the moon, and it does give you an appreciation for the engineering challenges that had to be overcome, the technologies that had to be built to actually achieve that remarkable feat. And when you think about what's happening now with technology in general, where we need to have a decarbonization of the economy, we need to have a green tech revolution in this country, that's going to be very, very heavily dependent on microelectronics.

We want to go back to the moon. We want to go on to Mars. We want to explore the solar system. [This is] very, very dependent on cutting-edge microelectronics. I guess it's a long way of saying that we're not going to accomplish anything impressive here on Earth or out in space without the ability to invent and build these technologies, and I think that there's a sense of national pride and ownership and a desire to lead in that space, while at the same time being part of a global economic footprint. You're right. And I'm a nerd about the space program, we could talk about that all day. But when I see this tech and I realize my iPhone has more capacity now than the computer that took us to the moon, you just realize how far we've come, and it's on the backs of engineers and some of our member companies that have invented this technology and are poised to do even more in the future.

MB: Along the same lines, HR 7677, which was a similar bill to 3249 that was introduced in the last Congress, defined PCB as a circuit board on which a pattern of copper foil connects the components. The text of the current bill defines PCBs as a composite with electrically conductive and nonconductive materials, so that opens the door to, among other things, additively manufactured or electronics printed with conductive inks. Was that the reason for the change?

Rep. Blake Moore (R-UT)

DS: One of the things that we did at the end of the last Congress was our coalition circled the wagons and said when we see this bill reintroduced in the 118th, what are some improvements to the language that can be made? I'm not an engineer. We went to our member companies and said, "Are we casting the net wide enough? Is this the proper modern definition?" Because what gets written into the law is what gets applied out in the field. With the CHIPS Act, there are very specific phrases, nouns and adjectives and verbs that define where these billions of dollars go. This wasn't something at the sort of administrative level that was worked out. Our member companies said, "A more current and proper definition is really XYZ," and I give a lot of credit to Chris Mitchell and the team at IPC for assisting in that. We also added substrates because we realized in the last bill that we were falling a little bit short by limiting ourselves to printed circuit boards, that three layers of the stack – the semiconductor, the substrate and the board – are all part of the ecosystem. Many board manufacturers are beginning to get into that substrate space and they wanted that expanded definition as well. I think the language was greatly improved and I thank Representative Blake Moore and Representative Anna Eshoo for making adjustments to that bill with industry input that now I think brings it to the state-of-the-art.

Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-CA)

MB: If I'm reading it correctly, 3249 funds the factory updates for one year. Does that suggest manufacturers need to be ready to go right away if it passes?

DS: What I'm observing is that private money is following public action and here's what I mean by that. The $52 billion that the CHIPS Act allocated is starting to be dispersed. You're going to see this over probably a decade, the entirety of that money get handed out, but what's amazing is how private money is coming off the sidelines in response to public leadership. There's by some estimates $400 billion in private money going into semiconductor construction, production capacity. I think that a number of people in our industry are waiting to see where the government goes. They're prepared to act. The business case only exists if the demand signal is there. The government can help make that demand signal. Think of all these things as a down payment.

Everyone acknowledges that the CHIPS Act is a start. People believe, and I certainly believe, that the PCBs Act is a first. I think our industry is nimble. I think it's ready to invest, but of course without a demand signal, the business case isn't there. We're operating in a marketplace, so I'd like to see this bill passed. I'd like to see the tax credit create strong demand, $3 billion be available to our members immediately, but we're going to be back revisiting this issue whether this bill succeeds or fails for years to come. Travis likes to say, "We took 40 years to dig this hole for ourselves. We're not going to dig out in four months." This is a long slog, and we're ready for it.

MB: We mentioned the NDAA a bit ago. It's different from the standalone funding bills, as you noted, and it just passed the US House. Any specifics in that particular bill that the industry should be made aware of?

DS: I think one of the things that we have been around for two years pursuing aggressively is DoD policy that protects American microelectronics and secures and builds resilient supply chains, and Section 841 and Section 851 of the NDAA specifically call on the Department of Defense to come up with a plan to secure their entire microelectronic supply chain, including commercial off-the-shelf technology.

Figure 2. Joint NASA-industry collaboration led to the first SMT boards.

We're all familiar with ITAR. We understand the rules that say that certain defense systems have to have American-made, trusted microelectronics. That's nothing new to anybody in our industry. But when it comes to commercial off-the-shelf technology, the supply chain becomes a bit opaquer. The trust becomes a little bit weaker. One of the things that we're calling on DoD to do by 2027 – that's the implementation date – is say we are going to look at our COTS supply chains and we're going to make sure that from certain adversarial locations, we are not in fact supplying critical defense systems. We've got to keep that provision sold. We've got to fight to make sure that's there every day through January 1st of 2027, when DoD has to actually implement it.

This is the reason we came into existence in 2021, and we've got to fight for it every year in the NDAA, but that's really the policy bill. That's the rules of the road. How do you run the DoD bill? The appropriations bill is the money, as you mentioned. We've got to go fight for at least $100 million in that bill as well. But Congress looks at everything that our men and women in uniform depend on and says, "We've got to be able to trust this stuff. We've got to be able to trust where the critical materials come from, where the microelectrodes come from, where is it made." And I think we exposed a potential flaw, a potential liability, and this is a good step to deal with it.

MB: Finally, advocates for passage of the Chips Act were successful, in part because of their outreach to mainstream media. Do you see a need to go outside the industry media as well?

DS: Oh, absolutely. You and others who cover the industry in detail have been tremendous advocates for us. You're shedding a lot of light on this issue, and I think even within microelectronics, critical materials suppliers, assemblers, manufacturers, there's a growing awareness that advocacy in Washington is critical to what we do. But yes, I'm openly envious of the way that the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times cover the semiconductor industry. Some of it has to do with size, of course. These are some of the biggest companies in the world and they're working in the "high B" billions, they're breaking ground on massive facilities and promising thousands of jobs in key political districts, I don't know that our impact politically or economically mirrors what they're doing, but they will tell you because I've sat with these that what we are doing is critical to the overall stack and supply chain. And I think we've had some very positive interactions, positive coverage in outlets like the New York Times, for example. I've spoken to Bloomberg a number of times about these issues. At the national level with tier one press and media, it's a competition to have your issue covered and to make sure that you're the shiny object of the day, but we are part of a broad story and as much as anybody wants to talk about there's always that question: "What's the rest of the story?" Well, we are the rest of the story, and I think we're beginning to get traction there. But we are eager to get the word out in any venue that will give us the time.

MIKE BUETOW is president of the PCEA (pcea.net); This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..