Can the electronics industry influence global trade pacts with China? And should it? The word from many major trade groups appears to be “yes” and “maybe not.”

Can the electronics industry influence global trade pacts with China? And should it? The word from many major trade groups appears to be “yes” and “maybe not.”

IPC, SEMI, the Semiconductor Industry Association and National Association of Manufacturers have each commented of late on the proposed tax hikes to be levied by the US on Chinese imports in response to concerns over China’s technology transfer policies and the massive trade imbalance between the world’s two largest economies.

Any action taken could be impactful in ways planned and unplanned, not in the least because China is likely to move aggressively to protect what has become a critical industry. In the first quarter of this year alone, China exported $138 billion worth of high-tech products, including finished goods, or about 25% of its overall exports.

IPC worries that tariffs will hurt its smaller members that procure much of their supplies from China. President and CEO John Mitchell says the proposed action “will increase production costs, delay product deliveries, and disrupt supply chains, imperiling US manufacturers and the jobs they provide.”

Instead of tax hikes, IPC is pushing the US Trade Representative to pursue bilateral negotiation and multilateral trade agreements, or to exempt raw materials and components that are typically sourced only from China. An IPC survey of US members indicated 87% of respondents import raw materials, components or equipment from China, with 58% saying the impact would be moderate or severe.

In its statement, IPC didn’t comment on IP protections or practices, focusing instead on the unrestrained flow of goods across the Pacific. By contrast, the SIA’s position was largely about IP.

In a public submission to the USTR, SIA noted semiconductor companies “face pressure to disclose or transfer” their IP. “Intellectual property is the lifeblood of the semiconductor industry,” wrote president and CEO John Neuffer. “Semiconductors are America’s fourth-largest export. US semiconductor companies … should be able to compete in foreign markets without putting their critical IP at risk.” While less specific than the IPC in its approach, SIA agreed of the need to “avoid tariffs that would harm competitive US industries and their consumers.”

While IPC and SIA issued statements, SEMI went to Washington to testify to Congress about the risks of a trade war. There, Jonathan Davis, global vice president of industry advocacy, said tariffs could cost the US tax revenue and jobs.

“These tariffs will undercut the ability of US semiconductor equipment companies to sell products overseas. This will reduce US exports. It will do nothing to solve our legitimate and longstanding concerns with China, and we believe that it will expand the US deficit with China. … In short, we believe these tariffs will cause significant harm to US businesses and technological leadership.”

The National Association of Manufacturers, another US-based trade group, acknowledged “that China’s theft of American intellectual property and their use of unfair trade practices represent clear threats to manufacturers’ competitiveness and the jobs of American manufacturing workers.”

NAM went a step further, however, saying tariffs are not only likely to mean new and significant costs for manufacturers and consumers, they “run the risk of provoking China to take further destructive actions against American workers.”

“If the imposition of tariffs is the first bid in negotiating a more level playing field, manufacturers believe the end-product must be a new, strategic approach that includes negotiating a fair, binding and enforceable rules-based trade agreement with China that requires them to end their unfair trade practices once and for all.”

And therein lies the rub. While the trade groups, for the most part, cite the need for revamping trade pacts, they do not suggest terms under which the playing field would be considered level. And it’s unlikely China agrees any change to the current protocols is needed. After all, it’s well-understood that China set out to capture a major share of the electronics supply chain, and has largely succeeded.

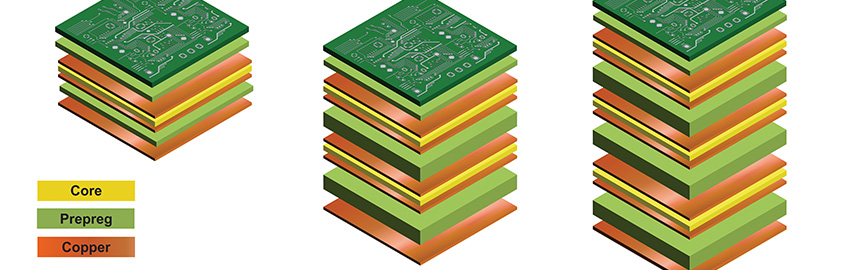

Going back 20 years, China was a growing but still relatively marginal player in electronics. Its annual PCB output was under $3 billion, and its share of the global market was less than 8%. Today its production is nearly 10 times that, and its market share is twice that of North America and Europe combined.

For semiconductor packaging equipment, China’s 2000 spend wasn’t enough to even rate a mention in the SEMI data. Today, it is the third-leading provider, with 14.5% of the nearly $57 billion world market. That’s easily ahead of North America (9.9%) and Europe (6.4%).

It’s easy to see why the trade groups are worried about inflaming tensions. But on this side of the pond, few agree the status quo is sustainable. So what’s the answer?

Can the electronics industry influence global trade pacts with China? And should it? The word from many major trade groups appears to be “yes” and “maybe not.”

Can the electronics industry influence global trade pacts with China? And should it? The word from many major trade groups appears to be “yes” and “maybe not.”