Making Simulation a ‘Snap’

A new online CAD library pairs specifications and social conversations in a dashboard-view of electronic components.

It was a little over 12 months ago that I first discussed SnapEDA with its founder, Natasha Baker.

At that time, Baker was about nine months removed from her job as a product marketing engineer at National Instruments. At NI, and at Analog Devices and Electronics Workbench before that, Baker worked on tools for printed circuit board simulation, modeling and land patterns.

Drawing from her experience, Baker saw an opportunity existed to capture what designers knew about components and how they perform electrically in real-world applications and redistribute that knowledge on a wide scale. And she wanted to do it via a vendor-agnostic platform and in a way that leveraged the best attributes of social media – the shared experiences – but in a highly targeted environment.

When we first talked, Baker, an electrical engineer, had the outline of her website and model in place and was busy learning programming to help put her vision into practice.

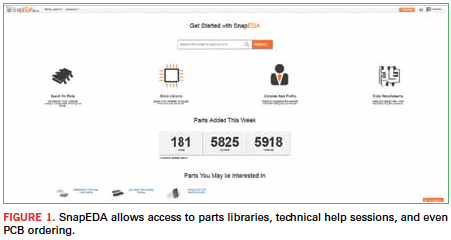

Fast forward to today, and Baker’s startup company, SnapEDA, has created a collaborative CAD library of schematic symbols, models and footprints. The platform goes considerably further than the seemingly ubiquitous crowd-sourced land pattern sites popping up all over the Web, however, branching into simulation models, and (hopefully, she adds) distributing semiconductor companies’ CAD libraries, simulation models and reference designs.

As with any user-generated and contributed library, there are risks, including bad data and IP infringement, intentional or otherwise. SnapEDA relies on its user community to vet everything that is shared. Users of the platform can download parts and vouch for their quality or flag problems.

Making the site vendor-neutral was a goal. Baker envisioned a platform based around the component itself, instead of being locked in to a particular tool. To that end, models and symbols can be exported to various software formats.

“Our overall goal is to be a comprehensive data source for everything someone might want to know about an electronic component, and a way to help them get started designing with that chip quickly, regardless of which design software they use,” Baker said. “So in addition to CAD libraries, we also provide datasheets and specifications, pricing and availability, and even questions and answers that have been asked about that component, all in the same view.”

Parts vetting. Users can share parts data by uploading them through SnapEDA, which has automation tools to simplify and speed the process. If a particular CAD part isn’t in SnapEDA’s database, the company has made it simple to request one from the community.

As part of the vetting process, the site indicates how many users have endorsed a component or model, and also how many users have flagged problems. Baker shied away from a star rating system, however, because its utility seemed vague. “What does it mean to give a part a rating of 3 stars? It’s a chip; either it’s right or wrong. It’s either a good CAD part or a bad part.”

Revealing exactly who has “vouched” for a part raises the authenticity of the endorsement. Moreover, the public stamp of approval implies the part has met their standards. Flagging, on the other hand, goes further than the traditional “thumbs down” vote, requiring the user to enter a particular issue they have identified with the part.

“If no one has endorsed the part, it is advised to proceed with caution and verify it against the datasheet,” Baker explains. “Down the line, we want to add more complexity to that, to provide rules on what makes a part good or bad.”

The data are free to use (and always will be, Baker adds). Down the road, SnapEDA envisions certain premium services, including a service for manufacturing and assembling prototypes. Crowd-sourcing is an easy way to get started, but Baker recognizes it as the first step in a longer process.

Of course, some designers are reluctant to upload parts data because their companies consider that their IP. Baker doesn’t see that as an issue, noting that the data regarding symbols aren’t proprietary. “A chip is a chip; a symbol is a symbol.”

An area of distinction is how Baker’s extensive experience with simulation and analysis tools comes into play. Users are encouraged to upload simulation models, which the community will also vet, and SnapEDA is engaging with semiconductor companies to distribute their CAD libraries, simulation models and reference designs. “It would be a trusted source of data on our side, and it’s a very targeted way for these companies to reach design engineers who are at the point where they are selecting products,” she says.

The networking side of the SnapEDA model is distinct from other sites as well. Baker set up SnapEDA as a full professional network, similar in some respects to LinkedIn in that each user has a unique profile that displays their professional credentials and specialties. As part of their “resume,” users can detail their specialization, for instance analog or digital design, or even more specific areas such as power supply design or high-speed PCB layout. They also can list the CAD tools they have expertise with. “This opens the doors for people to start having conversations at the design level,” Baker says. “It might be a message like, ‘I see that you are using the same CAD software as me. Do you know how to add a power pad to a footprint?’ or it could be a particular question about how to use a component in their design that another user of the site has used before.”

What users won’t do is vet each other. Instead, SnapEDA is focused on the components database, and using the social layer as a way to enable collaborative features around that database.

“The way we are implementing the community is around inciting conversations around parts. It’s not a community for general electronics; it’s targeted for designers,” Baker says. “It’s about, ‘I’m using this chip. I need to know how to use it, where to buy it from, and I’d like to download the libraries for my design so I can start designing immediately.’

“We have questions and answers on the site, but we direct people to ask questions around a particular electronic component that they’re using so as to direct the conversation in that sense.”

Certainly, countless technical conversations take place every day on various industry networking sites. But at no time has an effort been made to sort through, capture and make use of all those discussions. Yet SnapEDA is attempting to tackle just that. “The problem is if I’m on a forum and talking about a part, all that info is lost,” Baker says. “Maybe if you’re lucky someone will stumble upon it in a Google search, but otherwise all the information is scattered. But what if you could tie all that to the part to give users the context they need? That’s where the collaborative part really ties in. Then when someone else goes to look up information on a part – maybe a datasheet because they’re trying to troubleshoot a problem – they can see any other questions people have asked about it.

“Some, especially circuit board manufacturers that we have talked to, have been more hesitant to see the value in collaboration because they see how worried their customers are around the security of their designs, which is true and is a valid concern. But it blinds them to the fact that, on these forums, everyone is already helping each other, providing these very in depth technical solutions.”

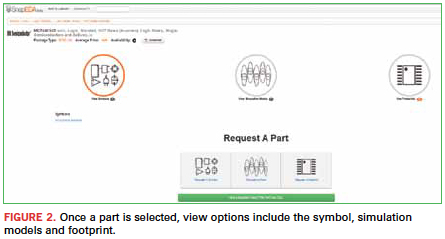

SnapEDA had a soft rollout in September. The software currently supports Altium, OrCAD, PADS, Eagle, Zuken, NI Multisim and KiCAD. In terms of conversion, most parts visible on the site can be converted instantly to Eagle, OrCAD, Altium and KiCAD. Baker adds that SnapEDA is focused on expanding to other conversion tools as it develops the community and develops relationships with CAD vendors. “We also show renderings of the symbols and footprints before downloading, so that users can verify the integrity of the data before they download it,” she adds.

What else does SnapEDA have in store? In addition to expanding its conversion tools, Baker wants to add editing capabilities to the symbol and footprint viewer, a move that would allow users to, for example, add a missing pin.

The company also plans to introduce a designs section, and better tools to help users discover new products. While currently focused on aggregating all the available knowledge about certain components, the firm wants to eventually help users find the right parts. “Right now we have parametric search, but we have other plans for the future,” Baker says.

Her biggest obstacle, Baker says, hasn’t been product development or market acceptance, but rather the more basic problem of knowing how to program. As a novice coder, she taught herself Django (a python-based web framework) and some other web technologies. SnapEDA has since brought on additional programmers. Ironically, for someone who is building a crowd-sourced database, Baker sees knowing how to do it yourself as a competitive advantage. “A lot of people outsource coding, which is fine, but having the expertise in-house makes you more agile and is very important if you’re committed to growing as a technology company.”

Mike Buetow is editor in chief of PCD&F (pcdandf.com); This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..